AN

UNUSUAL AND DIFFICULT JOURNEY

SEPTEMBER & OCTOBER 2019

In the City Hall lobby in Homer,

Alaska, is a small section of one wall dedicated to local history. In a small

frame on that wall is an orange-brown photocopy of a document cover more than a

century old. It is titled “Constitution and By-Laws of the Kings County Mining

Company of New York.” The story behind that document and its connection to

Homer and the central Kenai Peninsula requires a step back in time and all the

way across North America.

Two things are important to understand

from the beginning: First, the Kings County Mining Company originally had no

intention of going to the Kenai. Its advertised goal was the Klondike, in

Canada’s Yukon Territory, where gold had been discovered in 1896. Second,

shortly after the company launched its expedition in mid-February 1898, many

people believed it had ended in tragedy.

| |||

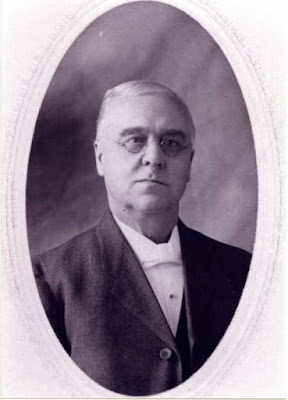

| Henry Walter Rozell,company treasurer. |

But not everything was what the way it

seemed. Changing plans and overcoming obstacles were going to be the norm on

this expedition.

Only about a week after the three-masted

bark, the Agate, had set sail from

Pier 4 in New York’s East River, this headline appeared in The New York Times:

“THE

AGATE’S OWNERS WORRIED.

Uncertainty as to Whether Wreckage

Reported Off Barnegat Is that of the

Bark.”

Barnegat

is a sheltered bay off the New Jersey coast. Floating

debris had been spotted

nearby, and early reports pointed to the Agate.

The well-financed dreams of the members of the Brooklyn-based mining company appeared

to have been crushed.

Fortunately

it was a false alarm. Shortly thereafter, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle produced a headline announcing that company

officials had determined the Agate

was safe after all; the wreckage, said the newspaper, had come from some other

unlucky vessel.

A few weeks later, in early April,

came a definitive sighting of the Agate

near Rio de Janeiro, off the coast of Brazil, still on course to sail around

Cape Horn and then northward to San Francisco.

Back

in New York, members of the mining company sighed with relief.

Reports

vary, but the Kings County Mining Company had approximately 60 shareholders,

all holding a financial stake of five $100 shares, for a total company investment

of $30,000 (about $828,000 in today’s money). They also had a 50-year charter

and plenty of optimism.

In

fact, the day before they had set sail, the Brooklyn

Daily Eagle had characterized the company as “made up of good businessmen,

all determined before they return to amass good-sized fortunes.”

To

help them realize their golden goal, the Agate

was carrying nearly all of the company’s gear—small steam-powered launch boats,

mining implements, tents, and about two years’ worth of provisions—plus about

30 members of the company, in addition to a captain and crew. According to their

stated plan, once the ship reached San Francisco, they would telegraph notice

of their arrival back to New York, and the remaining members of the expedition

would journey by transcontinental railroad to unite the full company.

But the

Spanish-American War, which also launched in 1898, complicated matters.

The

Spanish gunboat Temerario was prowling

the east coast of South America. Fearing that the American vessel might be

captured, the United States consul in Montevideo, present-day capital of

Uruguay, halted the Agate’s voyage there

and caused a considerable delay.

In

fact, due also in part to the heavy weather they experienced later while

traveling around the Horn, the Agate

did not arrive in San Francisco until late August. By the time mining company

members back in Brooklyn had clambered aboard a West Shore Railroad locomotive and

begun their journey westward, they were well behind schedule, and the season was

growing late.

August

became September and crept toward October. Members of the Kings County Mining

Company reconsidered their plans. Deciding they were too close to winter to

reach the Yukon gold fields, they aimed instead for the Kenai Peninsula and set

their sights on the burgeoning mining town of Sunrise.

Gold had been discovered in the Hope

and Sunrise area by at least the early 1890s. When word got out, miners had surged

in. In the spring of 1896, according to the Hope & Sunrise Historical

Society, 3,000 gold seekers sailed into Cook Inlet. By the summer of 1898,

there were an estimated 8,000, and, for a few weeks, Sunrise City, along

Sixmile Creek, with 800 residents, was the largest town in Alaska.

The

members of the Kings County Mining Company, cruising into the inlet in late

autumn, hoped to add to the population and get rich.

But even in this they were unlucky.

According to Alaska’s No. 1 Guide, a biography of Andrew Berg by Catherine

Cassidy and Gary Titus, the captain of the Agate,

“apparently intimidated by the prospect of navigating Cook Inlet … convinced

the group that Sunrise was easily reached overland from Kachemak Bay.” Therefore,

on Oct. 16, he deposited the entire company and its “mountain of supplies” on the

base of what is now called the Homer Spit.

In 1898, coal miners were living and working in Coal Bay,

on the inside of the Spit, but little else resembling civilization was evident.

Today’s city of Homer simply did not exist, nor did roads or bridges or

accommodations of any sort. The members of the mining company—including some

women and possibly some children—were on their own.

Slowly

they began heading generally north, according to Cassidy and Titus, “cutting a

trail and ferrying their belongings with packboards and handmade wheelbarrows.

Besides a large quantity of foodstuffs, such as casks of flour and bacon, they

had all of their mining equipment, including pans, picks, shovels and sledges.”

By

early November, they had reached a coal-mining operation at McNeil Canyon (now

about Mile 12 of East End Road). There, on Nov. 10, they amended their company

constitution and bylaws, naming new officers and a new board of trustees, and trudged

onward.

They

walked the beach to the head of Kachemak Bay, then traveled up the west side of

the Fox River drainage and over to Tustumena Lake. Around the eastern end of

the lake, they ascended the Birch Creek drainage to reach the benchlands

between Tustumena and Skilak lakes. After crossing the Killey River, they made

their way to the south shore of Skilak Lake and decided they could go no

further.

It

was winter. They hastily built cabins along a stream now known as King County

Creek, and they hunkered down.

In

the next spring, they gave up.

According to

Cassidy and Titus, they dissolved their company charter and built boats to

carry them downstream to Kenai. Most of them found their way back to the East

Coast, no fortunes in their pockets, in fact no mining done at all. And for

years afterward, trappers using the miners’ cross-country trail “found caches

of equipment and food which the hapless group had abandoned along the way.”

But

there is a coda to this tale of disappointment.

Enter

Hjalmar Anderson, who along with his wife Jessie, homesteaded Caribou Island on

Skilak Lake in 1924. According to mid-1970s documentation from longtime early

Homer resident Yule Kilcher, Anderson discovered the last cabin still standing along

King County Creek in the 1920s and found inside part of a diary and the mining

company’s 1898 constitution and bylaws.

Anderson

rescued the legal document, reported Kilcher, but left the remains of the diary

because it had been “used as fire kindling by Army Officers during World War I

who were using the cabin as quarters.” Anderson bequeathed the document to

Kilcher, and in 1976 Kilcher donated it to Homer’s Pratt Museum.

Kilcher

also told the museum that at least three members of the mining company had

remained in Alaska, although the exact number is difficult to pin down.

According to Cassidy and Titus, it was two: Carl Petterson, who settled in

Kenai and married Matrona Demidoff; and Herman Stelter, who was documented

living and mining in the Kenai River canyon in the 1910s. The phrase “Stelter’s

Ranch” can still be seen on old topographic maps of the area.

In

her History of Mining on the Kenai

Peninsula, Alaska, Mary J. Barry suggests there may have been at least one

more man who stayed, although she names no one else. Likely, though, it was

Thomas P. Weatherell, who in November 1898 had been tabbed as the mining

company’s new vice-president.

Kilcher

said that one of the men who stayed had moved to Talkeetna. In a history of

Talkeetna, author Coleen Mielke describes Weatherell, born in either 1869 or

1871, as “a bachelor from New York” who was the Talkeetna postmaster from 1918

to 1927.

As

for the Agate, it was sold and added

to the West Coast salmon-fishing fleet, according to a news brief in the March

1900 issue of the San Francisco Call.

And

53 members of the dissolved mining company, finding themselves without gold and

most of their investment, filed lawsuits that in 1903 ended up before the New

York Supreme Court. The court demanded that former company treasurer, Henry W.

Rozell, provide all financial records pertaining to company assets and

expenses, including the sale of the Agate.

|

| A hundred years after the Kings County Mining Company expedition of 1898, only a few cabin logs remained as evidence along what is now called King County Creek, near Skilak Lake. |